Disciplinary Literacy: Teaching Students to Think Like Experts

Our last issue introduced the Project GLAD® strategy, Directed Reading Thinking Activity or DRTA, to use with whole class reading instruction. This is a little gem of a strategy that can be differentiated with elementary classes but also has great potential in the secondary classroom when our focus is disciplinary literacy.

Disciplinary literacy is the idea that each subject area—like math, science, history, or literature—has its own language, ways of thinking, and methods of communicating. To truly master a subject, students must learn how to read, write, and think like experts in that discipline. It’s not just about content knowledge; it’s about understanding how knowledge is created and communicated within a field.

What Is Disciplinary Literacy?

Unlike general literacy strategies, which apply broadly across content areas, disciplinary literacy focuses on the specific ways reading, writing, and thinking happen within each academic discipline. For example:

A historian reads primary sources critically, comparing perspectives and evaluating bias.

A scientist interprets graphs, reads research studies, and writes lab reports using technical language and structured formats.

A mathematician deciphers symbolic notation, understands proofs, and explains reasoning clearly.

A literary scholar analyzes character development, theme, and tone with an eye for nuance and ambiguity.

In short, disciplinary literacy helps students go beyond surface-level comprehension and engage deeply with subject matter as insiders.

Why It Matters

Traditional literacy instruction focuses on fluency, vocabulary, and general comprehension. While these skills are essential, they’re not sufficient for success in content-rich classes, especially at the secondary level. A student may be an excellent general reader but struggle to make sense of a biology textbook or a historical speech.

By integrating disciplinary literacy into instruction, educators can:

- Help students access complex texts in meaningful ways.

- Develop critical thinking skills specific to each subject.

- Prepare students for college and careers, where disciplinary thinking is the norm.

- Encourage equity, by explicitly teaching the tools students need to succeed in academic environments often dominated by unstated rules and expectations.

Key Features of Disciplinary Literacy

Each discipline has its own norms, but there are common features that define disciplinary literacy:

- Text Structures and Features

Different disciplines use texts that are structured in unique ways. For example, scientific texts often use headings, charts, and data tables, while historical texts may include footnotes, timelines, or multiple source types. Teaching students to recognize and navigate these structures helps improve comprehension.

- Vocabulary and Language

Disciplinary vocabulary goes beyond definitions. Students must learn how terms function within the logic of the discipline. In math, for instance, the word “function” has a very specific meaning that differs from its everyday use. Teachers must help students internalize this specialized language.

- Purpose and Perspective

Each discipline has its own purpose for reading and writing. A historian reads to analyze cause and effect, point of view, and context. A scientist reads to extract data, verify results, or replicate experiments. Helping students adopt these perspectives fosters deeper engagement.

- Evidence and Argumentation

Experts in different fields use evidence in specific ways. English students support interpretations with textual evidence. Scientists use empirical data. Historians evaluate the credibility of sources and construct arguments based on multiple accounts. Teaching students how to construct arguments in discipline-specific ways is central to disciplinary literacy.

Moving Beyond Silos

One of the most powerful aspects of disciplinary literacy is that it encourages students to see knowledge as interconnected. A student analyzing climate change, for instance, must engage with scientific data, historical trends, and ethical debates. Disciplinary literacy helps them navigate this complexity with purpose and clarity.

In a world where information is abundant, but expertise is scarce, teaching students to think like experts isn’t just a classroom skill—it’s a life skill.

Let’s not just teach students what to learn—let’s teach them how to think.

Using DRTA to foster Disciplinary Literacy

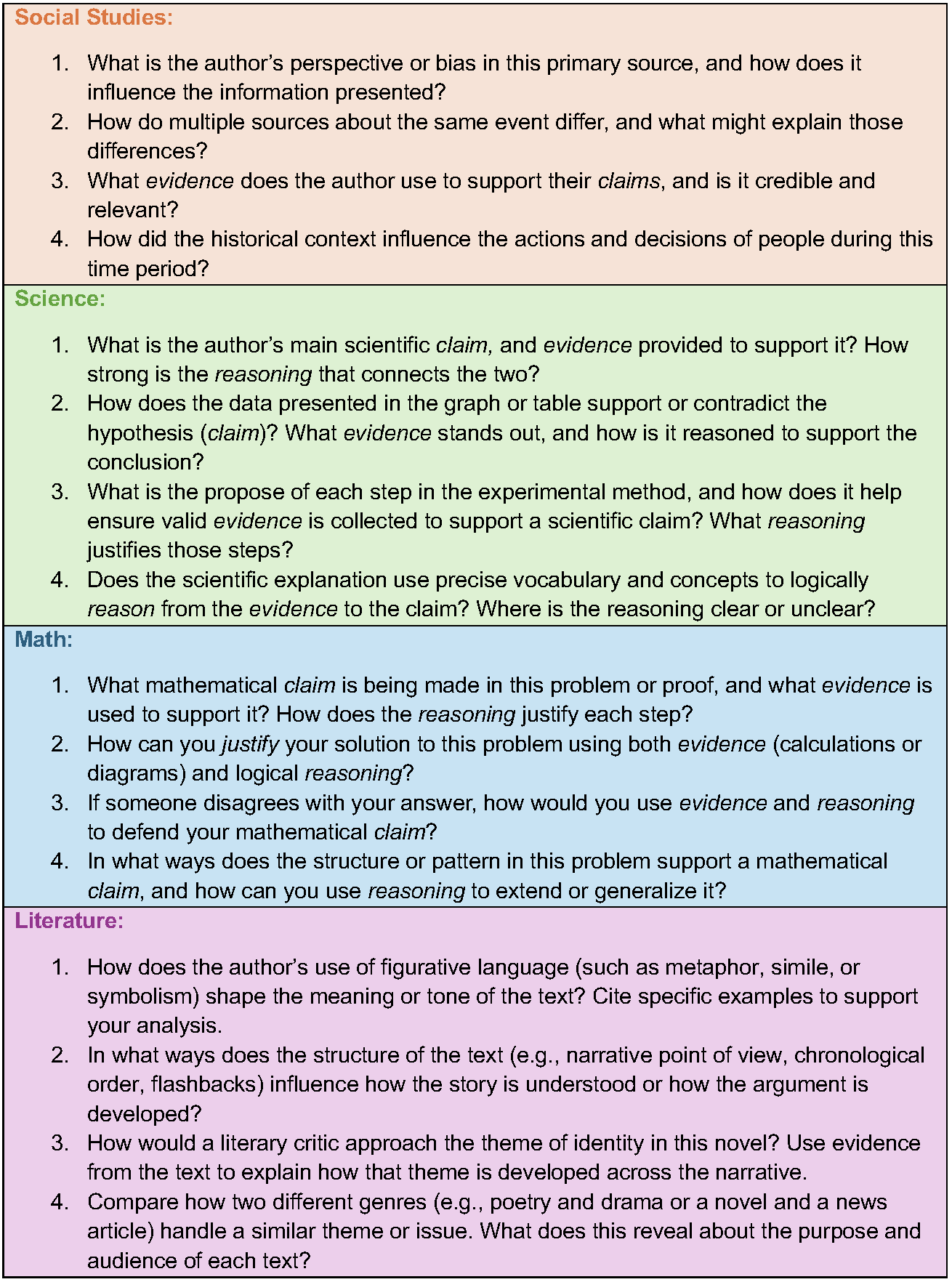

When using the DRTA strategy for guiding students through a complex text in the content specific classroom, use focused questions for your discipline.

D = Directed

Show students the cover of the text. Heads together to make predictions what the text will be about – what taking points and discipline-specific vocabulary will they encounter? What disciplinary literacy skills do they predict will be needed to interact with the text and what academic vocabulary helps discipline experts communicate ideas?

R = Reading

Students read up to a pre-selected stopping point. Discuss what they read and go back to refine predictions.

Teach language and text features specific to disciplinary literacy and scaffold ways to navigate a discipline specific text. Continue reading the text in sections. Anticipate where scaffolding will be needed.

T = Thinking

At the end of the text, students revisit their predictions and verify or modify them based on supporting evidence from the text.

Thanks for reading,

Jody and Sara

For more great strategies to help with your Project GLAD® implementation, visit us at nextstepsprojectglad.com