Cognitive Load

Sometimes interactions we have with students really stick with us, even months or years later. Especially, when we are left wondering how we could have taught differently to make the learning experience more productive, or comprehensible, or just plain better for that student.

I recently had that experience this summer when we facilitated an online training examining GLAD® strategies at the primary level. As I watched the footage of an expert group, I was reminded how that small group and the level of text was too much cognitive load for one of the students. We’ll call her Annie.

The same question is often asked by teachers:

How will my students do with expert text that is too high?

Cognitive Load

The concept of cognitive load is an essential framework in understanding how students process information and why some lessons resonate while others become overwhelming. It refers to the mental effort required to learn something new, and it’s shaped by the complexity of the material, the way it’s presented, and the learner’s own prior knowledge.

There are three primary types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane.

Intrinsic load is inherent to the task itself—the natural difficulty or complexity of the content. For example, learning advanced algebra involves more mental effort than basic arithmetic simply due to the nature of the material.

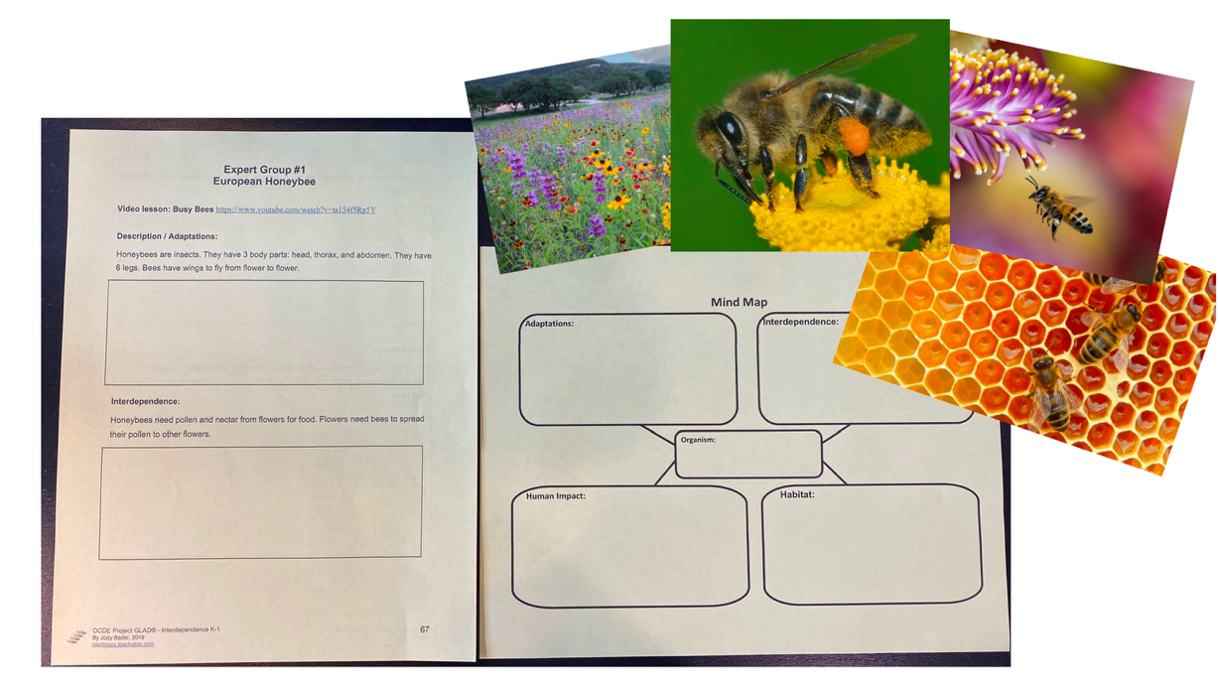

The topic of our expert group was the honeybee. Though the purpose of an expert group is for new information to be learned by one team member who then brings it back and teaches their team, this content wasn’t completely new. We read about the honeybee in our big book and talked about its habitat and interdependence with flowers on our world map. And we can assume that 7-year-olds have had some life experience with bees, so I don’t think Annie was having difficulty understanding the content.

Extraneous load arises from the way information is delivered; unnecessary jargon, confusing visuals, or disorganized instructions can increase this load, making learning harder. This includes how text is organized and its readability. Extraneous load can also include distractions in the environment when trying to focus on a task.

This is where Annie struggled. She was an emerging reader, and she was still learning reader behaviors – looking at the text, tracking with your finger, sounding out words. In other words, the intrinsic load of reading. She was very distracted by the group of teachers standing around our table watching the small group, as well as the rest of the class who were doing team tasks in other parts of the room.

The last type of cognitive load is called Germane. Germane load is the productive effort students invest in making sense of new ideas, developing patterns, and building deeper understanding. Effective teaching means balancing these loads: minimizing extraneous distractions, managing intrinsic complexity, and encouraging germane processing through meaningful engagement. Research suggests that when cognitive load exceeds a student’s working memory capacity, learning suffers. Students may feel lost, frustrated, or disengaged—not because they lack ability, but because their mental bandwidth is overwhelmed.

Strategies for reducing cognitive load include breaking lessons into smaller steps, using clear language, visually organizing information, and connecting new ideas to what students already know. Encouraging active learning—where students are guided to make connections and apply concepts—can also boost germane load and deepen comprehension.

An important component to the expert group strategy is using grade level text. Our main rationale is to teach notetaking and study skills. Expert groups is not a reading group. With that in mind, employing germane load to balance intrinsic and extraneous is an important consideration when your small group will be composed of a heterogenous mix of readers.

Expert Group Scaffolds

For Annie, the scaffolds we put in place helped her comprehend a text that would otherwise have been too difficult for her.

- The text was chunked into manageable sized paragraphs that were visually separated by blank boxes.

- We read the text out loud as a group. Some students were more fluent readers than others, but all the students were encouraged to read the words they knew.

- The students were also directed to track the text with their fingers as we read. In Annie’s case, the teacher helped track.

- We talked about each section after we read it, and we sketched important ideas we learned in the box under the text.

- Finally, we also had visuals and a graphic organizer available for comprehensibility.

Recognizing the impact of cognitive load helps educators design lessons that are not just informative but accessible, adaptable, and memorable. The trick is to scaffold the manageability of the task without compromising the thinking power students need to grapple with to make learning gains.

When we reflect on past teaching moments and wonder how we could have reached a student more effectively, cognitive load theory offers valuable insight for making future interactions more successful and supportive.

Thanks for reading!

Jody and Sara

Check out this year's line-up of our Project GLAD® offerings!