GLAD® and The Science of Reading III: Comprehension

🤯 Mind blown!

During my research on reading comprehension and how best to teach it I came across a series of podcasts that have changed my view of how best to frame the concept of reading comprehension. What is it? How do we acquire it? Can you teach it?

Dr. Sharon Vaughn is the Executive Director of the Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk at the University of Texas at Austin and the lead author of the What Works Clearinghouse Practice Guides.

Vaughn posits that comprehension can’t be taught. Rather, we help build it for students by, first, teaching them how to read the words and knowing what the words mean – phonics + vocabulary. Then, if the student has enough background knowledge of the topic they are reading about, comprehension is the result.

Tim Rasinkski of Kent State University, corroborates this assertion quantitatively, “90% of 3rd-4th graders who have problems with reading comprehension also have problems with phonics, vocabulary, and fluency.”

How a knowledge-driven approach helps comprehension

In the traditional model of reading instruction – ‘learning to read’ (decoding), then ‘reading to learn’ (gain knowledge) - the text is the conduit from which knowledge is gained. However, research shows knowledge and vocabulary are not only the results of developing comprehension skills, but contributors to children’s comprehension.

Knowledge can compensate for low reading skill and low cognitive ability in readers. When children who are generally weak readers are presented with a text on a topic they know a lot about, their comprehension is better than that of generally strong readers who do not know about the topic.

Cognitive models of reading show that the basis of strong comprehension is the ability to link information together to form a coherent picture. But text is full of holes. Holes are ideas not explicitly stated in the text. The reader must connect information between sentences and paragraphs to create a mental picture. You fill in holes with background knowledge.

Consider the sentence, “Brad forgot his sunglasses.”

The reader’s background knowledge will fill in the idea that not having sunglasses is a problem.

- People squint when the light is too bright

- Southern CA is bright and sunny. Brad lives in California.

- Celebrities are sometimes seen wearing sunglasses. Was not wearing them an intentional PR thing?

- Perhaps the flashing cameras that celebrities encounter are hurting his eyes?

These ideas are not stated in the text, but our background knowledge fills in the gaps. The reader can then integrate information across sentences to make inferences.

When presented with the next sentence, “He didn’t see the hazard ahead,” the reader will return to the previous information about Brad and previous inferences about not being able to see well because perhaps the sun was in his eyes.

Background knowledge is the key for reading comprehension because you can retrieve knowledge you already have and add to it. Dr. Hugh Catts of Florida State University explains, “You can only get so much information from a text because of the limitations of working memory. The advantage of background knowledge is that you can retrieve knowledge you have and add to it, so it doesn’t take up as much room in your working memory. This helps build a bigger memory.”

Inferencing comes naturally

Background knowledge also helps with inferencing, which was the process we just went through when wondering where Brad’s sunglasses were. The holes in text are where we connect ideas through inferences. Catts explains that inferencing is an automatic skill that humans do when they have enough background knowledge. It’s not something you can teach students to do, but it comes naturally when background knowledge is present. If the student knows nothing about the topic they are reading about, they won’t be able to make inferences and plug the text holes no matter how many reading comprehension strategies we teach.

Vocabulary and Comprehension: a package deal

This knowledge-driven approach also helps vocabulary, the other important component to comprehension. Vocabulary and reading comprehension are a package deal. You cannot have one without the other. If you can decode all the words in a passage but don’t know what some of them mean, your reading comprehension will falter. They should always be taught simultaneously.

The average student learns about 3000 words per year. For students in the lowest 25th percentile, that’s a 6000-word gap by 4th grade. It would take those students 5000 words a year to catch up. The single greatest thing teachers can do for the literacy development of MLs is to focus on vocabulary.

The trick is to teach reading comprehension and vocabulary through the content areas. We have to read about something. Why not read about what they are learning in science, history, civics, health, social skills, etc. Through the process of building knowledge, you are also building the breadth and depth of vocabulary needed to process and express those ideas.

This is what Project GLAD® is all about! Our model is packed with strategies for building background and explicitly frontloading content knowledge and vocabulary. Who knew they would also help foster reading comprehension? (Well, we did.)

GLAD® strategies for building background knowledge and vocabulary

We’ve written about Input charts before, but because they fit perfectly with this topic it never hurts to revisit and expand.

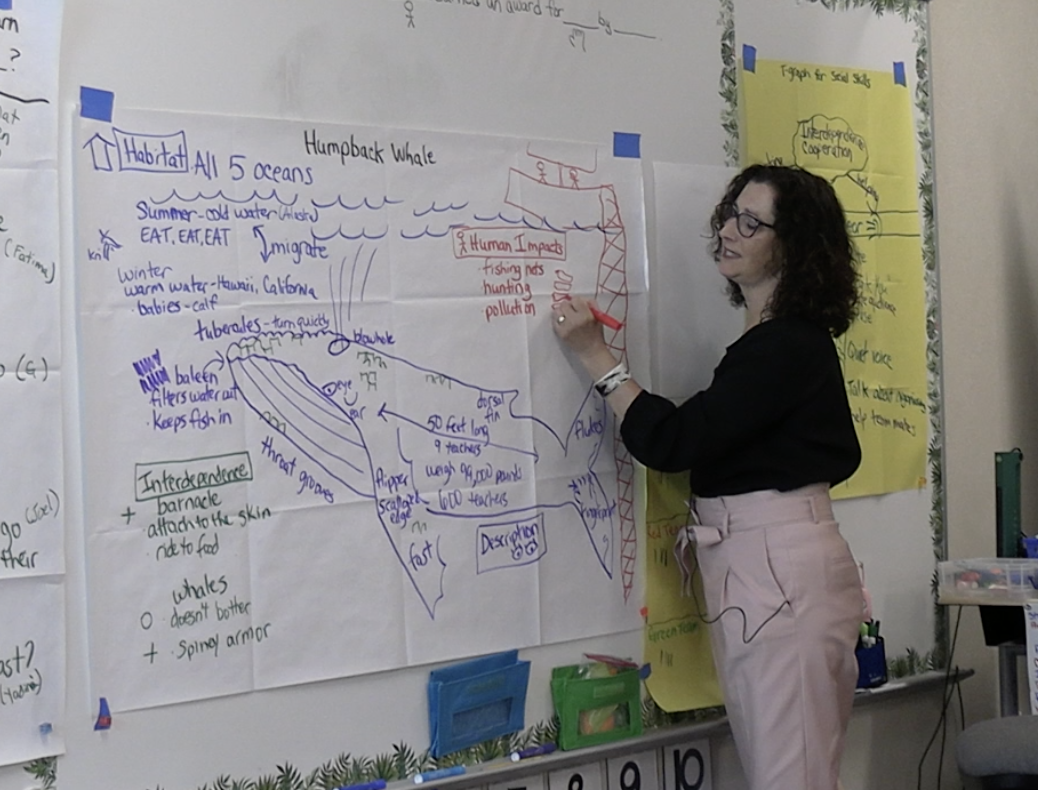

Pictorial Input Chart – One of our best-in-show strategies is the Pictorial Input Chart. The rationale for the use of this strategy is all about comprehensible input when delivering direct instruction of new content.

Incorporating comprehensible input practices into our lessons benefits all students but are essential scaffolds for our MLs. The pictorial is one of the main strategies we use in Project GLAD® to build background knowledge with students and embed direct vocabulary instruction. After multiple exposures to this content and vocabulary they will have the tools they need to comprehend grade-level text.

The Pictorial Input Chart can be classified as an anchor chart because it is a visual used during a lecture-style lesson and is left on the classroom wall as a content and vocabulary resource. The difference between a traditional anchor chart and a GLAD input chart is the layers of intentionality for developing knowledge and vocabulary.

What makes the Pictorial special?

- A pictorial is always created in front of students. They sit in close proximity during the input lesson. This means we bring them to the front of the classroom. In the elementary grades, “Meet me at the carpet,” is a common transition phrase. In secondary, we use a different transition, but the result is the same of bringing the students close. Every high school teacher will tell you that the kids in the front row pay attention better. So, let’s bring them all forward.

- A pictorial starts with a blank piece of chart paper that has been lightly pencil-sketched with the visuals, vocabulary, and conversation prompts we will cover in the lesson.

- The information to be covered has also been chunked into standards-based categories that the teacher visually discriminates using color. A different color for each chunk of information.

- Throughout the entire lesson and with great frequency, the teacher prompts the students to “say it with me” when new vocabulary is introduced. This pronunciation practice is combined with the image(s) the teacher is sketching on the chart, the written word that the students see, and even gestures. This creates multiple layers of scaffolding.

- At the end of each chunk of information added to the chart, the teacher also stops the lesson to give students an opportunity for verbal processing of that chunk with someone next to them. During this time students’ primary languages are permitted and promoted.

- We call this a 10/2. Humans can only hold about 10 minutes worth of new information in their working memory before some of it is forgotten to make room for new information. If we do something with that information – like talk or write about it – then it can be moved to long-term storage. Working memory is then freed up for the next chunk of new information.

There are follow-up activities to the Pictorial Input Chart to get students processing, applying, and writing. All of these are covered in much greater depth in our online offering Acceleration 401: Take It to Writing.

But, we’re not quite ready to put a bow on reading comprehension and call it finished! As you were reading this post, I bet you were wondering where to fit in all the reading comprehension skills that your curriculum/standards/districts/etc., expect you to teach. If comprehension is an outcome rather than a skill to be taught – then why teach it?

That will be covered next month. Until then…

Thanks for reading,

Jody and Sara

Sources:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/science-of-reading-the-podcast/id1483513974?i=1000457953504